Calculating the Real Cost of Operation Rio Grande

IN AUGUST 2017—three days after the launch of Operation Rio Grande (ORG) to ‘clean up’ the Salt Lake City neighborhood near 500 West—the ACLU of Utah published a statement on our website.[1]“Operation Rio Grande appears to be, at this point in time, ‘business as usual,'" we wrote. Noting the substantial focus on law enforcement, we described it as another ineffective attempt to address complex social issues like substance abuse and mental illness “through our broken criminal justice system.”[2]Media reports the same week noted how state officials secured 300 new jail beds prior to the operation but added only 37 beds for drug treatment programs.[3]With ORG designed as a hammer, we predicted 14 months ago that everyone it touched would be treated like a nail.

Download this report as a (PDF)

Watch the October 18, 2018 panel discussion about this report (Event page)

A Critical Appraisal

Operation Rio Grande’s 24-month timer will expire soon after the planned June 2019 closure of The Road Home shelter and its replacement with three dispersed homeless resource centers. With that deadline now eight months away, we believe a critical appraisal is necessary. This report will analyze three topics—the criminalization of homelessness; the burden of ORG on treatment programs; and the status- and place-based erosion of privacy and Fourth Amendment rights—to identify the lessons learned during the last 14 months to inform a new and better way forward.

We aren’t asking, “Is ORG better than the pre-August 2017 status quo?” We acknowledge how the Rio Grande neighborhood felt unsafe for many individuals, disrupted local businesses, and attracted criminals seeking to exploit people experiencing homelessness. But we believe ORG was a hurried and heavy-handed response conceived with little appreciation for its long-term consequences. Being homeless is not a crime, yet thousands of individuals living in or frequenting the Rio Grande neighborhood were detained, jailed, and released with no additional help and the added burden of warrants, fines, and a criminal record. Despite a few inspirational yet anecdotal success stories, the vast majority of individuals ensnared in ORG are no better off than they were before.

Part 1: The “Crime” of Being Homeless

The one-year anniversary of ORG in August 2018 generated conflicting reviews. Backers cited safer streets and people rebuilding their lives, while detractors criticized the large number of arrests and lack of drug treatment options. While state officials were cautious enough to reject a “mission accomplished” banner, they still highlighted data they claim shows significant progress. That approach wasn’t surprising given how much statistical evidence has defined the official narrative of ORG. Every month since the fall of 2017, the state has released pages of data charting the operation’s three phases: 1) Public safety; 2) Treatment access; and 3) Employment training. Details from the August 21, 2018 update (the latest available) are typical: a 42% decline in reported crime, 324 more arrests, 16 people entering drug treatment programs, 20 new residential treatment beds, and 28 employment plans.[4]ORG’s commitment to transparency is commendable. It is also helpful for identifying trends and problems that are missing and overlooked.

A Serious Imbalance

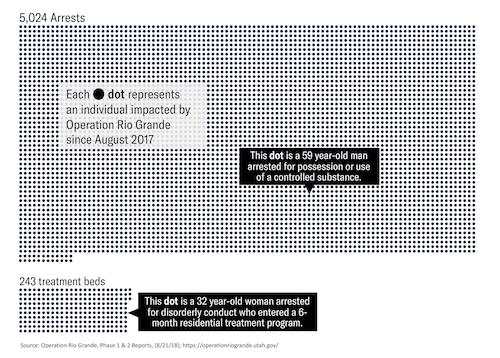

Since August 2017, more than 5,024 arrests have been attributed to Operation Rio Grande, with 79% of them associated with misdemeanors or active warrants.[5]During the same period, local social service agencies added 243 new treatment beds, while 120 individuals pled into a new drug court.[6]

The 13-to-1 imbalance is a direct result of the law-enforcement dominance of ORG from its inception. This disparity was predicted by more voices than just the ACLU of Utah, with one local elected leader emailing the Lieutenant Governor the day before the operation began to warn how “the short-term gain of a crackdown on drug crime without appropriate treatment and stabilizing resources brings long term-pain, as the fallout from merely arresting and jailing these individuals plays out in our community.”[7]A month into the operation, Iain De Jong, a nationally-recognized expert on homelessness, suggested that his prediction that ORG was focused on “criminalizing homelessness” had been proven correct. "They are adding additional barriers to housing and employment by adding more arrests to people who are homeless and already have many barriers to housing," De Jong wrote on his consulting company’s website.[8]It is now clear that the thousands of people churned through ORG during the past 14 months could have received better options and outcomes if elected leaders and law enforcement agencies had taken a different approach. The vast gap between those going to jail and those entering treatment could have been narrower. Instead, several high-profile incidents in the late summer of 2017 —including three homicides[9]—seemed to rush state leaders into launching ORG before either the local jails or treatment programs were able to handle the influx of people it created.

Missing the Target

Backers of ORG originally claimed its police sweeps would target the “worst of the worst” to drive away the area’s drug trade.[10]But a month into the operation, reporting by the Salt Lake Tribune detailed how just three of the 1,106 ORG-related bookings at the Salt Lake County Jail were for first-degree felonies, and only one-fifth had any felony charge at all.[11]Most charges were low-level, drug-related misdemeanors or active warrants. In response, an ORG leader told the Tribunethat law enforcement was instead targeting “expendable” individuals involved in the local drug trade.[12]Plus, although ORG leaders said officers wouldn’t arrest individuals for nuisance crimes like jaywalking, littering, or loitering—the ACLU has learned that police frequently rely on those minor infractions to stop, question, and search individuals. Mostly missing from the official narrative so far is the burden created by these thousands of new arrests, fresh criminal records, and increased jail time—due primarily to minor offenses. Laudable efforts to expunge criminal records through drug courts and periodic legal clinics staffed by volunteer attorneys haven’t eliminated the long-term collateral damage caused by over 5,000 ORG-related arrests.[13]At the same time that criminal justice reform is emphasizing reduced incarceration levels and more alternatives to jail, ORG has swelled local jail populations and made it harder for many people to rebuild their lives. Just as we stated in August 2017, the short-term, law enforcement focus of ORG, combined with a shortage of resources for drug and mental health treatment, has hamstrung the operation’s long-term goals.

Behind the Statistics

An indicator of ORG's success frequently cited by its supporters is the dramatic drop in overall reported crime. Notwithstanding the impact that flooding a neighborhood with hundreds of police officers and a helicopter circling overhead will do to people with bad intentions, their claim is accurate and an indication that ORG has narrowly succeeded with its primary goal to “restore public safety.” According to the Salt Lake City Police Department’s CompStat database, statistics for serious “Part 1” crimes are not only 39% lower in 2018 for the several square blocks impacted by ORG, but these crimes are also down 22% citywide and showing double-digit drops in the council districts that surround those blocks.[14]However, most appraisals of ORG fail to note that crime rates had been declining in Salt Lake City since a 2015 peak. In 2016—the year prior to ORG—Part 1 crimes fell 7.3% across the city, and 3.5% in the ORG area. Similarly, crime rates in 2016 declined between 5% and 14% in the districts adjacent to the Rio Grande neighborhood.[15]While it is possible to claim that ORG has accelerated an overall decrease in reported crimes, the downward trend in these statistics actually started 20 months before the operation commenced.

In addition, a more detailed analysis of CompStat reports could indicate that the law enforcement crackdown in the Rio Grande area is dispersing a criminal element out of that zone and into adjacent neighborhoods such as District #5 (Liberty Park) and District #2 (North Temple). Both of those districts have experienced post-ORG spikes in specific reported crimes, including residential burglaries,[16]but this analysis is beyond the scope of this report. More importantly, the correlation between homelessness and crime Is frequently and incorrectly comingled in discussions of ORG—a fact that likely influenced the law enforcement dominance of the operation from the very beginning.

We cite crime statistics in this report for two reasons. First, we want to point out the pre-ORG origins of Salt Lake City's decline in crime since 2015. Second, we believe that measuring crime within a specific area does not indicate whether the underlying social problems in that place are being addressed. A lower crime rate does not mean that more people have stable housing, access to drug treatment programs, or won't be stopped five times each morning by the police. Crime rates are a metric of place—not people—with a closer correlation to real estate values than to the physical and mental well-being of local residents.

However, the most compelling rejection of ORG’s reliance on declining crime rates as a proxy for success is public perception. A September 2018 poll of Salt Lake City residents commissioned by UtahPolicy.comindicated that 45% of respondents believed the homeless/panhandling situation in the city was “about the same” as before ORG began, with 24% claiming it was worse, and 26% saying the environment had improved.[17]The public can read statistics, but they can also understand what they see and hear in their city and neighborhoods.

Part 2: Access to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Treatment

The second phase of Operation Rio Grande aims to provide those affected by homelessness with opportunities to receive mental health and substance abuse treatment. At the outset of the operation, organizers promised an “aggressive prosecution with treatment options” and “referrals to enhanced community services.”[18]To achieve that goal, state and local government made significant investments to expand treatment beds and services, while Salt Lake County created an ORG-specific drug court to allow individuals to plead guilty to drug-related offenses and complete treatment with the goal of clearing their criminal history.

Has Phase 2 Worked?

The previously mentioned 13-to-1 imbalance between arrests and treatment placements (residential program beds and drug court pleas) suggests that the law enforcement aspect of ORG has been pursued more aggressively than the promise of referrals. Lack of treatment space is the primary challenge. The substance abuse and mental health needs of individuals detained by ORG far outstrip the capacity of local service providers. Ironically, jail is one place that people detained in ORG can access substance abuse and mental health treatment. Two well-regarded services for long-term ORG detainees are the CATS(Corrections Addiction Treatment Services) and DOGS (Drug Offender Group Services) programs. However, even jail-based programs aren’t a reliable option for most people detained in the operation because of similar capacity constraints. In October, Salt Lake County Sheriff Rosie Rivera told the Salt Lake Tribunethat 85% of people caught up in ORG should be receiving mental health treatment.[19]But according to the Tribune, 1,950 of the more than 5,000 arrests during ORG so far have resulted in release due to overcrowding.[20]This problem dates to the first month of the operation, when the Tribunereported how 171 out of 321 people arrested for misdemeanors were released due to limited jail space.[21]As a result, only a fraction of people detained by ORG qualify or gain access to these treatment programs either in jail or upon release.

In reality, ORG has merely exposed the unreasonable burden placed on Utah’s corrections system to diagnose and treat mental health and substance abuse issues. According to the Campaign for Smart Justice’s Blueprint for Smart Justice in Utah, the state's Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health estimated in 2015 that 72% of people receiving publicly provided treatment for mental health and substance use are involved in Utah’s criminal justice system. In 2015, 49% of Utahns voluntarily screened for substance abuse issues in jail needed additional drug assessments, while 40% voluntarily screened for mental health issues required additional assessments in that area as well.[22]

Another Approach

In contrast to the incarceration-focused approach of ORG, when Salt Lake City and County teamed up in September 2016 to launch “Operation Diversion”—a precursor effort to reduce crime in the Rio Grande neighborhood—they secured 62 treatment beds ahead of time and funneled people detained by police sweeps through an assessment center to match them with treatment options.[23]During our initial assessment of ORG, the ACLU of Utah noted it was "quite distinct" from Operation Diversion, citing the "prioritization of incarceration" over any consistent effort to connect individuals with assistance.[24]The most obvious and telling difference is in the names: “Diversion” was focused on guiding people to alternatives to jail, while “Rio Grande” aims to pacify an area of the city.

Like ORG, Operation Diversion struggled with placing the people swept up by increased law enforcement patrols in appropriate treatment settings. But the first operation’s smaller scale—hundreds of people detained instead of thousands—and its fundamental dedication to rehabilitation over jail allowed the treatment side of the operation to keep pace. According to a February 2017 Salt Lake Tribune article, the first four months of Operation Diversion resulted in 259 arrests, 84 successful treatment placements, 82 treatment drop-outs, a waitlist of 67 individuals, and 26 people falling into other categories.[25]The director of a local addiction treatment center characterized these results as “awesome.”[26]While the treatment numbers for Operation Diversion were considered a model for success, the additional demand for treatment beds created by ORG may leave many individuals unable to access the treatment they need to achieve stability, especially considering the added barrier to long-term stability. Plus, like the four-month report on Operation Diversion, we need more data on how many individuals detained by ORG have completed their treatment programs or drug court requirements. Despite these shortcomings, the hundreds of new treatment beds secured by ORG do far more to address the root social causes of homelessness than the surge in arrests and detentions.

The Road Ahead

A focus on the past and present have dominated the discussion of ORG so far. But many questions remain about ORG’s long-term impact on the lives of people impacted by arrest, incarceration, and the promise of treatment options. We know the thousands of criminal records created and lengthened by ORG will outlast the June 2019 expiration date for the operation. Will expungement remain a viable option for those whose criminal records endure beyond the conclusion of ORG? Will the one-time funding that enabled the expansion of substance abuse and mental health services continue after political leaders shift their attention to other priorities and upcoming elections? Will employers and landlords provide job and housing opportunities for individuals who now carry an arrest record? Will the next steps in criminal justice reform and reducing mass incarceration be applied equally to all populations, including those experiencing homelessness and substance abuse?

Reaching a comprehensive solution will require continued and multilateral efforts from mental health and substance abuse experts, business leaders, and government officials long after ORG officially ends. One immediate step could be Proposition #3, the Utah Medicaid Expansion Initiative. If passed by Utah voters this November and implemented by the state legislature next year, Proposition #3 could provide a partial solution to the challenge of securing reliable and long-term funding for ORG-related treatment options. Another factor could be implementing the lessons learned from The Road Home in the design and operation of the new homeless resource centers. Lastly, ORG organizers should focus more attention and resources on the service providers who now control the success of both ORG and what follows it. Fortunately, many of ORG’s stakeholders have previously recognized the importance of a collective impact model in solving complex issues like substance abuse and mental health. As June 2019 and ORG’s expiration date approaches, it is essential that ORG returns to these roots.

Part 3: The Erosion of Rights for People Experiencing Homelessness

In public places in Utah, a law enforcement officer can ask a person for identification without suspecting the person committed a crime. In those situations, a person can refuse to provide identification without consequence and walk away from the encounter. Law enforcement may, however, demand identification if a person is suspected of committing a crime, which includes minor infractions. In these instances, a minor violation like jaywalking can place an individual in a situation where an officer has a right to demand information that may result in an arrest.

Constantly in the Crosshairs

The police encounter described above has been repeated hundreds—if not thousands of times—on the streets of the Rio Grande neighborhood over the last year. As reported in the Salt Lake Tribune, law enforcement began to regularly ask pedestrians near 800 West and North Temple Street for identification soon after ORG began.[27]The article noted that many of the people police spoke to were experiencing homelessness, and that they were asked for identification multiple times a day. Although asking for identification is lawful and seems innocuous, consistently targeting persons that appear to be experiencing homelessness raises several concerns.

First, continuous police contact creates an atmosphere where people feel harassed or threatened, especially when a person is not suspected of committing a crime. This type of atmosphere divides law enforcement and the community and makes people wary of interacting with police officers. In ORG, this divide is extremely problematic given the stated purpose of the crackdown was to provide resources to the vulnerable population in the Rio Grande neighborhood through police contact.

Second, police encounters initiated primarily because a person appears homeless create a de facto criminalization of homeless populations. Purported consensual police encounters can be fishing expeditions for criminal conduct, even minor examples, that can lead to an arrest, jailtime and, eventually, a conviction.

Third, the effects of a conviction, even for a minor crime, can ricochet through an individual’s life creating dozens of collateral consequences. These harms may include ineligibility for financial aid for education and scholarships; ineligibility for licensing opportunities such as dieticians and massage therapists; and barriers to housing and government assistance. These and other collateral consequences may be burdening the 2,237 people arrested during ORG for misdemeanor offenses from August 2017 to August 2018.[28]Additionally, although ORG emphasized providing housing for people experiencing homelessness, only 178 people received short-term housing and only 101 individuals received long-term housing according to the latest data.[29]

A Place Becomes a Crime

The three concerns outlined above—continuous police contact, targeting of homeless individuals, and the collateral consequences of a conviction—result in the Rio Grande neighborhood—the space itself—being criminalized. People that previously had lived and received services in the neighborhood no longer felt welcome and dispersed to other neighborhoods and cities. Homeless populations forced to move have greater difficulty accessing resources and services, such as mental health treatment and subsidized meals. Plus, the dispersed population often faces the same issues with being over-policed in other communities.

In April, KUER reported how the South Salt Lake Police Chief claimed that monthly police contacts in his city increased from 42 to 232 after ORG started.[30]TheSalt Lake Tribunereported in August how Midvale police now take a “zero tolerance” approach to people experiencing homelessness in their city.[31]The article described how officers proactively removed homeless camps and required people lounging under trees to relocate to nearby parks. The same month a person experiencing homelessness explained to FOX13 how law enforcement force homeless persons to get off the streets and go to a park. But when the displaced people congregate at a park, more police arrive so “everyone gets scared and they run,” the man explained. Imagine this happening a dozen times each day and you have the reality of living with ORG.[32]

Moreover, people experiencing homelessness often need police protection more than they need to be policed. A 2014 study titled Violence and Victimssurveyed people who had experienced homelessness in five U.S. cities. The study found that 49% of respondents were victims of violent attacks, while 72% of those respondents claimed they were attacked 1-3 times while homeless.[33]Additionally, people with signs of mental illness are twice as likely to be arrested as people without a mental illness for the same behavior.[34]Future efforts to reduce homelessness should emphasize treatment beds rather than jail beds to more appropriately address its causes and to avoid the lingering consequences of criminal convictions.

Isolated From Help

ORG’s overarching goal to improve the Rio Grande area “for those individuals seeking supportive services to overcome homelessness” is at odds with its tactics that erode civil rights and criminalize spaces for those experiencing homelessness.[35]ORG has created a situation where a substantial portion of a vulnerable population has been pushed through the criminal justice system and/or into areas farther from services rather than towards treatment or housing assistance programs. Significantly more people have been arrested than have received treatment for mental health or substance abuse issues, which is disconcerting when we consider that a significant portion of people arrested in Utah struggle with those issues.

Conclusion

Despite the shortcomings of ORG highlighted in this report, the ACLU of Utah believes there is still time to make changes. The leaders of ORG can restructure its priorities and redirect its resources to target the underlying causes of homelessness and increase access to mental health and addiction treatment. Plus, the investment by state and local governments, together with service providers and advocacy groups, must continue beyond the two-year period defined by ORG to achieve a measurable level of success. The 13-to-1 imbalance between ORG arrests and placements in treatment services should be a wake-up call that this crackdown is creating more and longer-term challenges for people experiencing homelessness even as it attempts to help them.

We believe that population-level impacts, not anecdotes, should be the measure of success for programs like ORG. With increased investment in alternatives to incarceration, along with additional and sustainable funding for substance abuse and mental health treatment, the success stories of ORG can move from anecdotes to the norm.

The report was authored by Jason Groth, Zach Berger, and Jason Stevenson. Jason Groth is the Smart Justice Coordinator at the ACLU of Utah, where Jason Stevenson serves as the Strategic Communications Manager. Zach Berger is an intern working for the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice in Utah.

[1] ACLU of Utah Statement on Operation Rio Grande, (8/17/17), https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-utah-statement-operation-rio-grande

[2]Ibid.

[3]“‘Operation Rio Grande’ leaders scrambling for drug treatment beds as police prepare to launch crackdown,” Salt Lake Tribune, (8/11/17)

[4]Operation Rio Grande Update (8/21/18), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov, (accessed 10/15/18)

[5]Operation Rio Grande Update (8/21/18), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov/ORG_phase1.pdf, (accessed 10/15/18)

[6]Operation Rio Grande Update (8/21/18), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov/ORG_phase2.pdf, (accessed 10/15/18)

[7]“Who is being arrested in Operation Rio Grande? Many have felonies or lengthy records, though few appear to be the promised ‘worst of the worst,’” Salt Lake Tribune, (9/18/2017)

[8]“An Alternative Perspective on Operation Rio Grande & the Criminalization of Homelessness,” (10/16/2017), https://www.orgcode.com/opriogrande

[9]“Man shot to death in Rio Grande neighborhood,” Deseret News, (8/4/2017)

[10]"Jail Records Show Arrests On Rio Grande Mostly Low-level Offenses," KUER, (9/18/2017)

[11]"Who is being arrested in Operation Rio Grande? Many have felonies or lengthy records, though few appear to be the promised ‘worst of the worst,'" Salt Lake Tribune, (9/18/17)

[12]Ibid.

[13]"New Rio Grande outreach aims to help people clear their criminal records," Salt Lake Tribune, (2/25/17)

[14]Salt Lake City Police Department CompStat, (accessed 10/15/2018), https://slcpd.com/open-data/compstat/

[15]Ibid.

[16]Ibid.

[17]"Poll: Salt Lake City residents don't think homeless situation has improved," UtahPolicy.com, (9/25/18)

[18]Operation Rio Grande Flyer, (2017), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov/OpRioFlyer.pdf

[19]"With a crowded jail, where to house inmates will be a big challenge for the next Salt Lake County sheriff," Salt Lake Tribune, 10/7/18)

[20]“Crime is down in Salt Lake City, but police say Operation Rio Grande shifted homeless people to other areas," Salt Lake Tribune, (8/14/18)

[21]"Who is being arrested in Operation Rio Grande? Many have felonies or lengthy records, though few appear to be the promised ‘worst of the worst,'" Salt Lake Tribune, (9/18/17)

[22]Blueprint for Smart Justice in Utah, Smart Justice Utah, page 9, (September 2018), https://www.smartjusticeutah.org/blueprint.html

[23]"'Operation Diversion': Separating 'wolves' from vulnerable in Rio Grande neighborhood," Deseret News, (9/29/2017)

[24]ACLU of Utah Statement on Operation Rio Grande, (8/17/17), https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-utah-statement-operation-rio-grande

[25]"Early results: Operation Diversion having some success for homeless," Salt Lake Tribune, (2/11/17)

[26]Ibid.

[27]“Utah cops stopping homeless to see their ID, but are they breaking the law in doing so?,” Salt Lake Tribune, (10/18/17)

[28]Operation Rio Grande Update (8/21/18), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov/ORG_phase1.pdf, (accessed 10/15/18)

[29]Operation Rio Grande Update (8/21/18), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov/ORG_phase3.pdf, (accessed 10/15/18)

[30]"Operation Rio Grande: How Two Cities Are Dealing With The Fallout," KUER, (4/9/18)

[31]"Crime is down in Salt Lake City, but police say Operation Rio Grande shifted homeless people to other areas," Salt Lake Tribune, (8/14/18)

[32]"The success of ‘Operation Rio Grande’ one year later depends on who you ask," FOX13, (8/14/18)

[33]“Exploring the Experiences of Violence Among Individuals Who Are Homeless Using a Consumer-Led Approach,” pg. 126, Meinbresse, Molly, et. al., Violence and Victims, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2014, Springer Publishing Company, LLC.

[34]Ibid., pg. 131

[35]Operation Rio Grande Update (8/21/18), https://operationriogrande.utah.gov, (accessed 10/15/18)

Related content

ACLU of Utah Statement on Operation Rio Grande (UPDATED)

September 19, 2017

Calculating the Real Cost of Operation Rio Grande

November 8, 2018

Endgame for Operation Rio Grande

November 4, 2019Statement on Salt Lake County Sheriff’s “Operational...

April 3, 2017

The ACLU of Utah Comments on the extreme immigration proposal by...

November 26, 2024

2024 Impact Report

September 3, 2024

ACLU of Utah Calls for Enhanced Language Access for Limited...

July 8, 2024